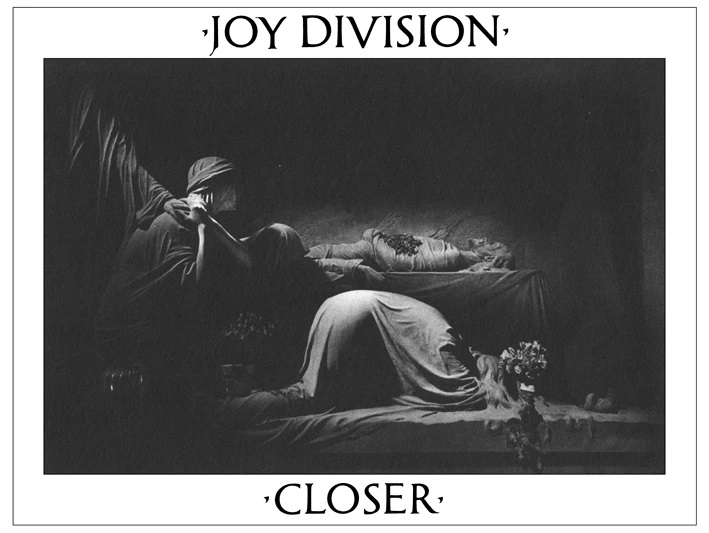

Shortly after the suicide of Joy Division’s singer, Ian Curtis, their label owner called their graphic designer, who literally had a grave realization. “We’ve got a tomb on the cover of the album,” Peter Saville told Factory Records’ co-founder Tony Wilson. “Oh, f@*k,” he replied.

The cover of the band’s second and final album, Closer, which was already in production, features a family tombstone at the Staglieno Cemetery in Genoa, Italy. Bathed in shadow are carved sculptures of the Virgin Mary, St. John, and Mary Magdalene mourning a recently slain Jesus. Which could arguably double as guitarist-keyboardist Bernard Sumner, bassist Peter Hook, and drummer Stephen Morris mourning their late singer.

Some listeners and journalists took it that way; they accused Factory Records of tastelessly advertising Curtis’ death, despite the fact that Closer’s cover had been chosen by the entire band weeks prior when Saville showed them a magazine full of photographs of the tomb by Bernard Pierre Wolff. “They all crowded around the drawing board and turned the pages,” Saville says in the band’s 2019 oral history, This Searing Light, The Sun, and Everything Else. “They were still four friends in something together; nobody was more important than anyone else.”

Forty years after its release, Closer mostly deserves its reputation as Curtis’ last will and testament. “This is the way, step inside,” the 23-year-old instructs on “Atrocity Exhibition,” as if he’s the ferryman that rows new arrivals to Hades. While the music is nothing if not morose, there’s more than depression and death under its hood, from literary inspirations to Martin Hannett’s innovative production to the psychological phenomena experienced by its main architect.